Custom keymaps in GNOME 3 on Wayland 2017-08-28

Why I care about keyboard modifiers

This is a merry dance.

One of those things I generally expect to be part of the routine of running a linux desktop is a certain amount of manual effort necessary to keep things running smoothly. Sometimes this is the classic multi-decade horror story of "sound card" configuration. Sometimes its the inevitable friction between under-specified hardware and volunteer-maintained drivers. Sometimes it's the CADT principle, where everything changes around you, just because it can, as part of the generational cycle of collaborative software development. Sometimes it's just the self-induced consequence of having a system where you can tweak and configure everything to work however you'd like it to, and therefore you choose to, and sometimes that's quite a deep rabbit hole. This tale covers a small handful of these categories, although it's primarily a consequence of that lattermost case.

Mod life

Mod keys. Modifier keys, that is. Those would be the keys you hold down alongside other keys to change their behaviour. The most obvious and venerable of these is SHIFT. Hold that down and type an alpha-numeric key, and you generate a different character. With the alphabetical keys, you GET THE CAPITAL LETTER FORM. Other keys, like the numerals, get you punctuation. You may also be aware of the Alt/AltGr modifier keys, which hang around on most keyboards, and generally allow access to a different shift level, further symbols and accented characters. And then there's control, or CTRL. Maybe you know that guy as the menu-shortcut accelerator key, or maybe for a couple of shortcuts you might use in the shell, if you're a shell user. Actually the kids all call it 'terminal' these days, because that's what Apple does. And then they all use iTerm anyway, for I don't know why really but I'm sure it's great. Anyway, calm down Mac-loving readers, this story is about how terrible linux is, you're all wonderful. So CTRL in the shell - CTRL + C cancels things, CTRL + D ends a session. CTRL + A takes you to the start of the line. CTRL + E takes you back to the end. Assuming you're using a fairly standard bash shell. Those last two are slightly more interesting, and immensely relevant to this story.

Enter Emacs

They're readline bindings. Readline is a GNU library used to make command line shell editing a little more interactive. And because bash is the GNU shell, it uses readline by default. Those keybindings are the default readline bindings, and they work the same in any application that uses readline. Typically this means other interactive shells. These keybindings are taken from Emacs. Emacs is a text editor, that is to say it's an application for interactively working on so-called 'plain text' files. Not that's there's any such thing as a plain text file. Emacs is one of the most ancient, convoluted, complex, crufty, awkward pieces of software you're ever likely to encounter. It's one of the original fundamental components of the GNU system. You might say it was the standard editor. Emacs is also one of my all-time favourite things. So those readline keybindings we were discussing, are intended to bring some of the more capable text editing commands from the GNU text editor across to the GNU shell, making use of modifier keys. Emacs really really likes modifier keys.

Because Emacs is a very old piece of software, it's design was heavily influenced by the keyboards typically used on the systems of its time. Computer use was a lot more text and command oriented, and the large, pre-PC era keyboards tended to reflect this by having a large amount of mod keys and function keys available. Commonly cited examples are the MIT or symbolics lisp machine 'space cadet' keyboards, and the Knight keyboard. As a consequence of this emacs can understand a lot of different modifier keys, and has a UI that is organised around layering functionality onto different keyboard 'chord' operations. You really need at least two distinct mod keys as a bare minimum to get emacs to do anything useful at all. We already met CTRL a couple of paragraphs back, but you also need another key called META. Emacs uses them in fundamental, and interestingly composable ways. For example, you can move the cursor forward one position by typing CTRL + F, but you can move the cursor one word forward by typing META + F. It's powerful, and sort of intuitive once you understand the fundamentals quite well. Unfortunately, they mostly stopped making keyboards with META keys on them some while back.

Welcoming the X Window System to the fray

Now I am getting quite old, but I'm not ancient enough to have run emacs on pre-Internet era hardware. I did use it a little bit on 7-bit serial terminals, and limped along using ESC as a prefix modifier, like a farmer, but by the time I started really learning how to use emacs to any serious degree, I'd made the jump to UNIX machines using X11 as a graphical user terminal. Some of the UNIX workstations had a META key. Some of them didn't, but had a few other modifier keys. Increasingly, UNIX graphical workstation started to mean 'Linux and XFree86 on PC hardware'. Now IBM-derived PC keyboards don't have a META key and never did. The original PC keyboards didn't really offer many modifier keys, but by this time period, everything had mostly standardised on the 101/102 key IBM extended model archetype. This doesn't have META keys, but it does have a pair of prominent ALT modifier keys. And so, we begin to remap.

X11 is maybe one of the canonical reference points for design by committee. Fully intended to offer a portable graphical , networked user interface across a variety of dissimilar UNIX systems, it tries very hard to offer the broadest possible set of abstractions across similar base behaviours, trying to build a unifying API in all aspects. Screen dimensions and orientation, color model and layout, pointers, input devices, key-types, you name it. So you can usually configure your equipment in a bewildering, verging on frustratingly flexible manner. X11 is a very broad church and welcomes all kinds of keyboards. X11 allows you a whole byte for modifier keys (I think), so you can have Shift, Lock , Control, and then five others called Mod1 through Mod5. You can freely map key codes onto key symbols, and then assign key symbols to one or more modifiers. So obviously this all took fourteen hours to decipher in the first instance, but I gradually became reasonably adept at using the Xmodmap utility to set ALT to be both ALT and META, CAPSLK to be another CTRL and life was mostly good. You'd tweak your .Xmodmaprc file every time your keyboard changed significantly, load it in as part of your login, and everything would work. PC-104/105 keyboards came along, with windows keys, and this meant that you could perhaps add a SUPER or even a HYPER key, and bind those to other emacs macros. The system was working, and everyone got rich on the proceeds! Or not. Nonetheless, although linux desktop software was fairly terrible, it was a fine environment for running Emacs, and running Emacs was where most of the work got done after all.

A detour into Macintosh

Times have changed however, and systems have changed, and uses have changed, and so have I. Like everyone else, I started using laptops more. Modifier keys started getting scarce again, as the machines shrank down to be portable, and interfaces just grew ever more graphical. For about a decade, I used Macintosh systems, which represent their own series of keyboard configuration challenges. Macs are actually pretty good for modifiers, if I'm being fair - they have their own dedicated command key for all the system key shortcuts, and so you're free to map control and option as you see fit to control and meta. They even give you a little GUI configurator for managing and assigning modifier keys, which is way more convenient than spending hours searching for information about xmodmap. The main suckitude is that they don't have a symmetrical set of them on their laptop keyboards. You don't get a right hand CTRL. Symmetry is important for healthy typing habits with key chords, because it's vastly better for your hands if you use both of them for combinations. So you ideally want to be able to hold down CTRL META SUPER or some combination of them with one hand whilst you type the activation keys. So CTRL + C is best expressed as a right hand finger holding CTRL, whilst your left middle finger taps the C. So my life as a Macintosh Emacs user was constantly blighted by crazy-ass schemes to find keyboard layouts that allowed unstressful ways to type CTRL key combinations.

Desktop Linux in the present day

For the last few years though, I've been back on the linux horse (and why is a different story, for another day), and my main laptop, a battered lenovo ThinkPad, has a full set of three modifiers either side of the space bar, where they were intended to go. The Debian GNOME 3 desktop is configured to use the windows and menu keys for desktop commands, and the ALTGR key, which I have on the right, as some kind of compose prefix. Even thought it's X.org now, not XFree86, and Xmodmap is heavily deprecated in favour of the XKeyboard and Xinput extensions, using the GNOME configurator and then some of my old Xmodmap ways, I could make this go away, and map ALTGR to a right meta, ALT to a left meta and the windows and menu key to SUPER and HYPER. The lenovo x220 I use has a particularly excellent keyboard and all was right in the world.

And then GNOME 3.22 switched to Wayland as a display server, rather than X. And this year's Debian defaulted to this. Even though there is an X11 compatibility layer, GTK+ and GNOME on Wayland do not talk to X11 directly for mediated key events any more, and this meant that Xmodmap can't be used to universally set modifier maps. GNOME 3 on wayland will still use xkb for key configurations, and this meant another fourteen hours of fiddling about in order to come up with a keyboard scheme that works for both GNOME and legacy X using the XKeyboard extension (XKB). This was not made any easier by the fact that all the attempts to search for information on this get bogged down in legacy explanations about Xmodmap or how to enable XKB for X11. But I got there in the end

It seems like there's not actually any supported, or easily documented way to load user configurations into GNOME 3 + Wayland's XKB environment, so I ended up slightly disappointedly hacking them into the system options files. Of course this meant that several months after I did this, a system upgrade overwrote all of my changes, and I was left without a keyboard, and a scant recollection of how I ever did it, or what any of the bits were even called.

Finally I fix it

So this morning I figured out how to assemble it all again from first principles. To make it more worth my while, this time I decided to transpose all of the mod keys as I went, so I can have CTRL on the inside of META as it was originally intended to be, and push the other modifiers to the outside edge. To save myself the bother the next time this breaks underneath me, I thought I'd write down the exact sequences here. I am not going to try and attempt to explain XKB here. There are a several documents on the web that do that job, to varying degrees of success. I'm not going to pretend that I understand how it all works, I just experimented with xsetkbmap and xkbcomp under an X11 desktop until I understood how to express what I needed to work under Wayland. Here are the steps.

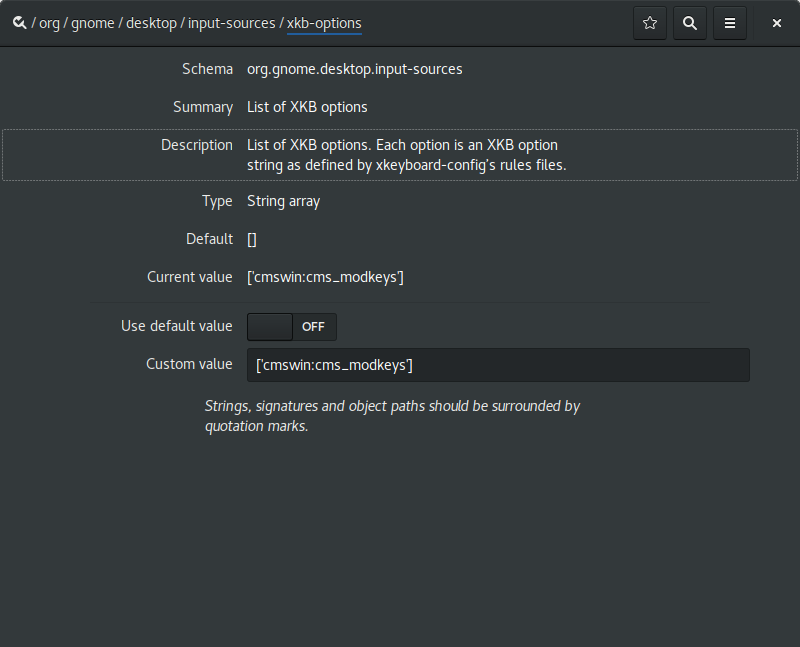

System-wide keyboard configuration is fine for configuring the basic keyboard layout - using the Debian keyboard configurator, I can pick either a ThinkPad or a pc-105 model with a gb layout. The modifier layout can then be selected using xkboptions. I can tell GNOME what XKB options to apply from its database, using the dconf configuration key /org/gnome/desktop/input-sources/xkb-options.

If you're playing along at home, you may have spotted that cmswin is not the name of any valid xkb layout. The wrinkle is that none of the built-in options offer quite the right set of combinations. So this is how I added my own custom XKB option.

1: Define an option

I added a new file usr/share/X11/xkb/symbols/cmswin to define my partial keymap.

Its contents:

// alts are ctrls, winkeys are metas, ctrls are supers

partial modifier_keys

xkb_symbols "cms_modkeys" {

replace key <LALT> { [ Control_L, Control_L ] };

replace key <LWIN> { [ Alt_L, Meta_L ] };

replace key <LCTL> { [ Super_L ] };

replace key <RALT> { [ Control_R, Control_R ] };

replace key <MENU> { [ Alt_R, Meta_R ] };

replace key <RCTL> { [ Super_R ] }; };

}; // end

that defines the option.

2: Add it to the rules database

Further to this, I modified /usr/share/X11/xkb/rules/evdev

adding the line

cmswin:cms_modkeys = +cmswin(cms_modkeys)

to the section

! option = symbols

I believe this is adding an option named cmswin:cms_modkeys to the dataset assigning it to parsing the 'cms_modkeys' entry from the 'cmswin' file, in the symbols subdirectory. The convention in xkb is to name all the different symbols using the same substrings, and it's terribly confusing when you're trying to remember which part does what, although slightly helpful when you're trying to perform the reverse map and locate which file is responsible for which option, I suppose.

3: Make it available for GNOME

The final step is to add the line

cmswin:cms_modkeys fix keys for emacs

into the file /usr/share/X11/xkb/rules/evdev.lst

I think this does something like import the option into the environment. There is also an evdev.xml file in the rules directory, which looks like it marks up the options to be used by the GNOME gui, but I didn't bother with that one, because life is too short to hand write XML for computers to parse, and I'd already spent half a day setting this all up. To give you an idea of how tedious this all was, for a while I'd added the evdev option into the section marked !option = types rather than symbols, and this caused wayland to stick to a crash loop as soon as I loaded the XKB option into the dconf key (with no visible error logs! yum!)

4: Retire, rich from the proceeds

With all of this in place however, everything works fine. For now. GNOME seems to be in a bit of a transitory phase with regards to keyboard and input configuration, it looks like they're reworking everything to use IBUS in the long term, so I expect I'll be doing some form of this dance again within a year. Until then though, this document can serve as a reference for the next time I, or anyone else interested enough needs to figure out how to do this.

2017 then, and nothing seems to have really changed that much at all. Desktop Linux is still terrible, and desktop linux is still awesome. Emacs is still terrible, and Emacs is still the best tool I have.