Shibboleths 2025-06-04

I Asked AI to Rebase My Git Branch and Accidentally Discovered the Future (and Uncovered the Past)

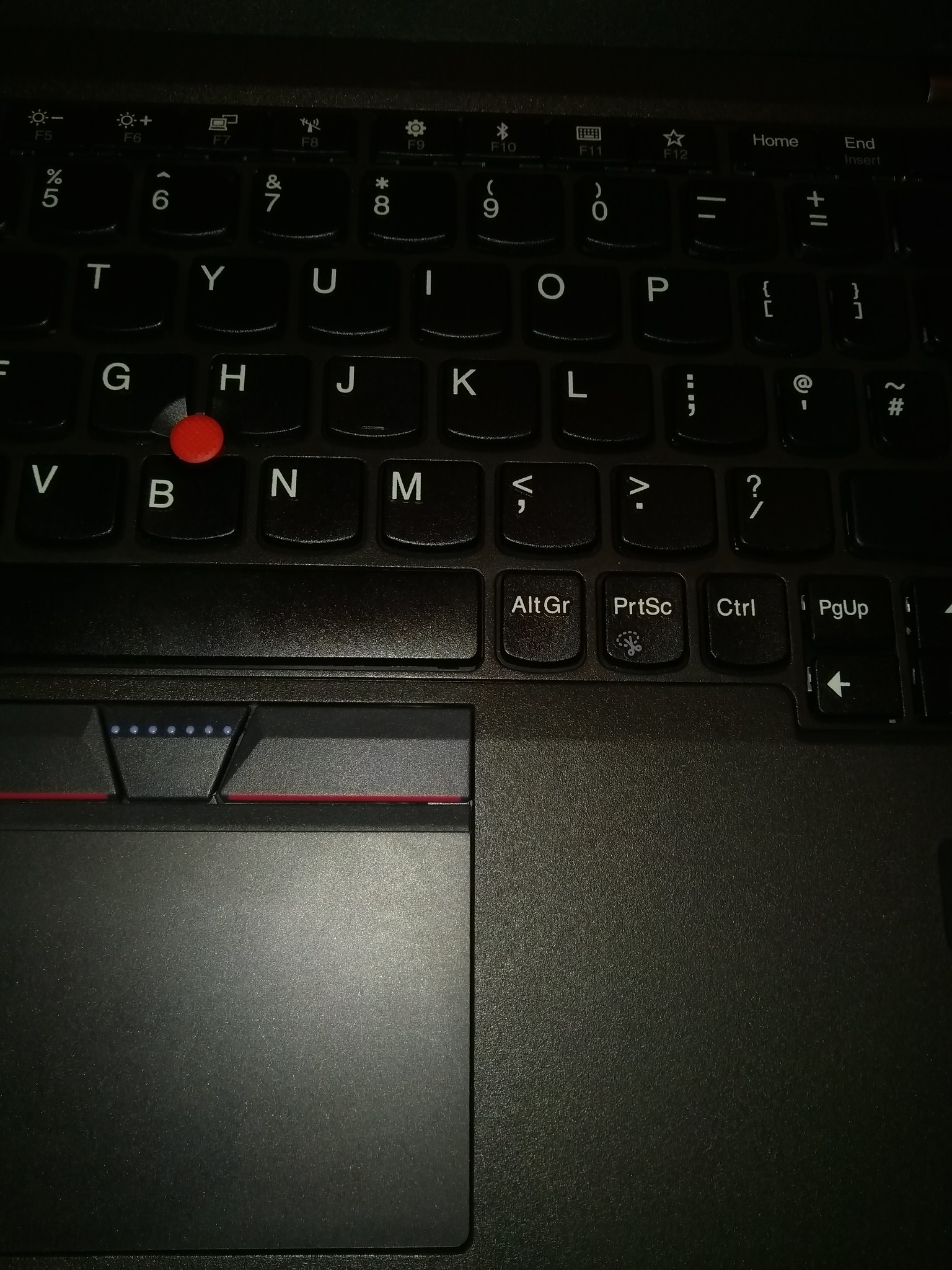

One of the things I initially missed most, when shifting from emacs to zed was magit, which has been my main git interface for IDK, let's say about 20 years 🤷.

I'm a bit of a sloppy worker, but a meticulous git user, lots of atomic annotated commits, many linear branches, I'm cherry picking and rebasing, and stashing, and magit integrates all of this naturally into the normal flow.

Zed has git integration, obviously, but it's entirely basic - pull, push, commit, branch, diff, that's about it. It does let you stage incrementally, which is most of the problem solved, and of course, there is a terminal integration, so you can pop a shell and use git CLI (like a farmer 🤪).

It's OK, but clunky, obviously. A little bit of friction and dissonance in this slick world of modern native editors that were actually made this century. I think the kids are a lot looser with git than I am, and perhaps they have a point, but I like the discipline.

Here comes the machine mind

You probably figured out what's coming next, if you bothered to read this far.

I've been using the zed LLM integration to write commit messages for a while - it's pretty well suited to that, given a bit of context, you can generate a draft commit message that summarises the changes, and it's you tweak and approve them before you apply. It's a pretty good example of the kind of low-hanging, small improvement, you can achieve with even simple model, precisely applied to a narrow context that involves generating prose. Smoothing out busywork.

Obviously, zed is pretty agentic 🤢, because that stupid word is all the rage these days. I guess you can open a chat box and ask your editor to vibe code your whole application. (Good luck with that, if you do, I think that's liable to create more work in integration than it saves in writing, maybe that's just me)

I use the agents for a bit of boilerplate here and there - refactor this, replace these magic numbers with proper constants, redo this part to use an iterator, what is the type checker complaining about here, how do I configure the language server to disable a misfeature, again, it's not too bad at doing think kind of drone effort, and there is a small but appreciable productivity gain to be had.

I cross the streams, and surprise myself

This last week, I was suddenly inspired to cross the streams, and something interesting happened, surprising me enough to bother drafting a post on the topic. I don't really like to thought-leader, but occasionally something will delight me enough to want to share.

I wanted to tidy up a messy WIP branch that collected a couple of different ideas in progress, (and had also coincided with me correctly figuring out how to enable auto-linting in zed, so I suddenly had a lot of aesthetic formatting corrections dropped suddenly into an already untidy sandbox)

A minute or two fiddling with rebase in magit, but in zed...? Time to roll up my sleeves, and flex, and take out the ol' git pitchfork, or hitch up the rebase propagator to the reflog tractor (I do not really know what farmers do). But, wait. I wonder if...

So I pull up the agent and ask it "can you run an interactive rebase on this branch please, and group all the white-space only changes into one commit, the other formatting changes into another, and then separate the removal of the obsolete class from the other feature work?"

And, it kind of worked! It got stuck a couple of times, and I had to pop in and edit a couple of things, and I restarted it over with the order of the commits I wanted a little more explicitly instructed once I recognised where the conflicts were going to land, but I got the result I intended, certainly with no more fiddling about than I would have had to do if I'd been performing the task manually, maybe less? It's hard to measure, but I enjoyed the experience.

One thing I definitely realised. It was less irritating. I was able to complete a disruptive, yet necessary chore, while in the middle of doing something more interesting, with much less context switching than performing it manually. And that got me thinking about interfaces a bit more. Chat bots are unquestionably a very ergonomic interface.

Increasingly, I am starting to think that a key part of unlocking the value of LLMs, may be through thinking about them more as solutions for interface design problems.

Considering git interfaces

Git is a classic case. Git's interface sucks space balls, everyone knows it. I mean I know a few people who like it, and I'm happy for them (but I think they are weirdos). It does allow for a bunch of studly machismo and nerd flexing, for anyone who has invested enough time in learning its arcana to impress people with stunt-git trick shots, and that can be fun. I have definitely enjoyed being the knuckle-cracking "stand back everyone and stop panicking, I know how to fix this" guy on a number of occasions, but that is a sideshow. You can do circus tricks with power tools, and some people do, but it's not the reason the tools were made.

Git has a compelling storage model, and a commit graph workflow that solves a bunch of annoying challenges with incremental and concurrent code editing and integration, efficiently and better than previous source code version systems. That's why it became a huge success.

Git's horrible ergonomics and implicit barriers to entry, but compelling powers of sharing and integration, allowed GitHub to spring into existence, as a multi trillion zillion company from out of nowhere, just by slapping a nicer set of user abstractions on top of git's ugly robotic core. (in the process accidentally inventing some other significant ergonomic problems, like pull request based workflows, and IDK, tag driven releases, but I guess that's a different blog post)

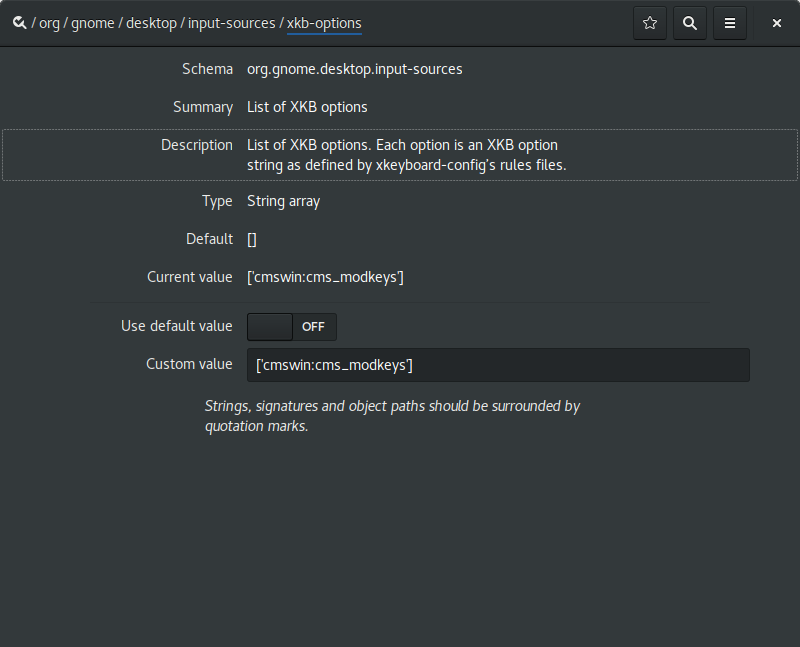

Git's foul ergonomics are what pulled me into learning magit, which has a reasonably steep learning curve of its own, but also follows the emacs way of having a lovely manual. It's a better thought out UI. It also leverages many common emacs behaviours, so when you're working in emacs already, which I typically was, again, you get this reduction of context switching.

The mythical 'Flow State'

Why is this so important? At this point, it's tempting to dive off into a side bar about "programmer flow state", a long held shibboleth of the developer community about which I don't have much truck, but many thousands of words can be found about it on the web already. - I don't like anything that reinforces programmer identity as a higher state of being, and I dislike how easily this concept is weaponised towards shunning collaboration and social work (e.g. "coders must not be interrupted during holy flow state") , again this is clearly a different adjacent blog post - but the notion is not fundamentally baseless.

Programming tasks often require holding a lot of accrued context about a chain of thought, and carefully expressing those in a narrow, precise domain, incrementally progressing towards a well defined future state. It's not easy for a human mind to do that, it takes a bit of effort. Effortlessly breaking out of one domain into another mode of expression isn't really possible. To do that even passably well, perhaps you would need a different kind of "mind", even?

I think version control is interesting here, precisely because it's liminal stuff. It's programming-adjacent work in a certain sense, it's a chore - any time you have to break thread to address some version control nonsense or busy work, you are in essence interrupting yourself. It makes a lot of sense to try and find a low friction simplified user interface to mediate these kind of tasks. Like GitHub, or magit. The ideal is to minimise the amount of disruption you face while working on these background or side channel threads of work. You can mitigate against this in two main ways I think. You can look for ways to simplify the UI to better suit a particular working context, as we have been discussing; alternatively you can divide the work and make the secondary context a first class task that's managed separately.

One way to do this is to structure the way you work so you can plan your version control stories a little ahead of time, and use discipline in your task management to make it better fit onto the VC, with strategies like formal branching and ticketing protocols, rigorous task mapping that accounts for tech debt, probably integrated into a project management system.

Another way you can do it is to make it literally someone's job and push the load out sideways - examples of this might be code review protocols, gatekeepers for merges (in the olden times, with less sophisticated version control software, I've often worked on teams where there was a nominated 'merge master', whose entire job, or a large portion of it would be to basically do the integration and harder version control work on behalf of the feature developers), also other adjacent roles like scrum masters, or DBAs.

How about SQL ?

That train of thought got me thinking about SQL. I think SQL is another interesting example of 'programming-adjacent work', although it might be a bit more subtle of an example than it first appears. Let's have another digression then. I really like SQL, although it's obviously covered in warts and sharp edges, I've always appreciated it's utility, and to a certain extent it's ergonomics. It does share some of the properties I've discussed with git - it's very often a boundary, and context shift away from the main thread of programming, and programmers tend to hate it, and like to avoid it, and make up nasty memes about it for slack, and that kind of thing - just like version control (or meetings 😘), it's essential and necessary work in a lot of software development, but it's another liminal place, where you have to get pulled out of the context of thinking about your feature work, and software architecture, and land in another place for a while with an annoying external syntax, and a lot of aggravating round trips into different tooling.

Indeed, over the years, a very common programming pattern is to try and slap a more program-ergonomic abstraction layer in front of the SQL, once again to try and minimise the friction and narrow the interface - I'm thinking of things like various ORMs, 'noSQL' database engines that bring the data modelling and querying closer to the application layer, all of them moderately successful, and yet SQL still hangs around everywhere, slightly annoying everyone, like a remote senior cousin inevitably invited to every wide social gathering, tolerated, rather than enthusiastically invited.

That's because SQL is already an ergonomic abstraction. It's kind of the ur-DSL. SQL is there because databases have a lot of inertia associated with them. All the data is often where the money is. Data is the raw stockpile of materials, the raw ingredients of the information that's necessary to run large information technology applications. Data tends to accrue value cumulatively, and you want to keep it all in a big lump in one place (this is why we have terms like 'data-mining' and 'data-warehousing'), so you can correlate it, and leverage sexy network effects from having it all integrated into one humongous data domain. Once you pass a certain critical data mass, you need to access it multi-modally , i.e. there will be many different use cases for the same information sets, different users and different applications will emerge from, or require access to, various intersectional pieces of that data blob. Now, reading and updating that data blob by hand, in your preferred programming stack would really sting. You'd still have to leave your application software context, but you'd now need to delve into a world of low level file systems, and data packing, and indexed data access, and write locking, and concurrent editing, and wire protocols, and cache invalidation, and the whole nine yards of that side of computer science.

I pause a little here, because I realise I'm probably making it sound kind of fun to a particular audience segment (amongst which I include myself, periodically), but let's not lose track of the core point. If your intended task is to make a cool dating app that helps your users get laid, low level storage systems coding is a horrible, high effort context switch away from the feature track you're working on. And of course, all this data access code you're having to do while you go will also need tracking in your version control system, more context switches. Instead, we SQL.

LLMs suck at SQL though

As an aside, I have found LLM coding assistants to be generally pretty bad at SQL writing. I have two hand-wavy personal theories about why this is the case

- Programmers, on average, in my experience are really pretty bad at SQL, probably because of the reasons we delved into above. So the training set of the models is full of low quality material. (cheap shot, maybe? 😅 Cut me some slack, I've spent many hours of my life fixing other people's bad SQL)

- Effective SQL generation requires a lot of external context the model doesn't have - not only the entire database schema, but also ideas about the data contents, and distributions that a pre-trained model doesn't necessarily have any access to. I think getting good SQL results from LLMs would need a lot of context prompting, or specific training. Still doesn't entirely explain why they're so bad at basic join syntax.

I'm tempted to infer something from those two sub-points about SQL requiring fundamentally different kinds of reasoning to other forms of writing, but I'm probably just seeing the face of Poseidon appearing in the patterns of my mental sea foam... I'll leave it there for now. (a third parallel blog post? This stuff is getting fractal). BTW - The name for that fascinating phenomenon is *pareidolia* , and it's something worth keeping in mind when discussing "AI" concepts...

The surprising invention and nature of SQL

Ahem... Another really interesting aside is to have a look back at the history of SQL. SQL is rather old. It's basically my age, and I've already pointed out I've been using emacs professionally for at least a few decades. SQL emerges from IBM in the 1970s, as a research project, greatly influenced by E.F. Codd's classic article 'A relational model of data for large shared data banks'

The primary designers of SQL were Don Chamberlin and Ray Boyce, part of IBM's system R research project, who were tasked with looking into ways to apply Codd's relational / mathematical principles of database modelling to IBM's database businesses. IBM's database business at this point was most of IBM's business, and IBM's database business was pretty huge. Prior to relational databases, the existing big iron database management systems were awkward weird transactional / hierarchical databases, like IMS/360 where you pretty much had to write a specific computer program to be batch executed from a queued transaction management system. Each 'query' was more akin to an independent program. In order to change the report, you'd develop a new program, and you would need appropriate programmer time and skill to do it, and your best turnaround for results would be several hours, probably more like days.

So the system R researchers wanted to make this more flexible, but their ambitions didn't end there. Chamberlin and Boyce wanted to make information retrieval accessible to non-programmers. Here's Chamberlin

"Ray and I hoped to design a relational language based on concepts that would be familiar to a wider population of users. We also hoped to extend the language to encompass database updates and administrative tasks such as the creation of new tables and views, which had traditionally been outside the scope of a query language.[...] What we thought we were doing was making it possible for non-programmers to interact with databases. We thought that this was going to open up access to data to a whole new class of people who could do things that were never possible before because they didn’t know how to program."

Can you see where I'm heading? SQL is a frantically successful example of what we used to call '4GLs', (fourth generation languages), when I was a school kid, (although by that point, the text books - and what we didn't yet call the hype cycle - were already breathlessly excited by the imminent arrival of the Fifth Generation Languages, and systems...). The terminology is dated, and stretchy, and marketing-fed, but the central gist is - 4GLs are languages that were operating at a higher abstraction level. Your inputs and controls would describe a program at an abstraction level much higher than the operation of the system, and the 4GL would write a program for you that ran at the lower level. All a bit hand-wavy, but SQL querying has some really interesting properties related to this delegation.

- it's declarative. Your query describes the data structures you want to retrieve, and the actual details of how the data is retrieved from disk is decided for you by a query planner.

- it's live and interactive - you can interrogate the system interactively at a REPL

- it's got a weird-as-hell syntax full of special cases that tries valiantly to use ENGLISH LIKE words, all IN UPPER CASE SHOUTING that deal in terms of database structures and relational operators, not computer terms like bytes and loops and sorts.

The query planner is worth a little thought - The query plan uses a bit of maths, and some heuristics and a bunch of information and sampled data about your system, and works out a series of reads and sorts and filters that produce the data structures your query is requesting. Crucially you don't tell it HOW to do it, just WHAT you want it to do. (sorry, the upper case is a bit addicting, I'll stop). Most of the time you don't think about it too much more than that. However, most SQL database systems will show you their plans if you ask them, typically by using the EXPLAIN keyword, which will show you what the planner thinks it should do to build the result set you wanted. If you don't like what it's decided you can't tell it to do things differently, but you may teach it to do things differently, typically by updating the available indexes and constraints, or maybe by re-balancing the statistics it uses to decide about cardinality and seek times, and that kind of thing.

Here again we have a division of labour - the idea is that the structural and statistical and optimising and runtime bits of maintaining the SQL system can be delegated to the programmer and technician classes, who can be more concerned with the implementation and operational parts, and the query writer (a non programmer, if you remember) can just get on with expressing their tasks in a lower friction, narrowed domain, where they don't have to context switch out as hard from their task at hand, writing lovely business reports for the sales and finance teams to make slide decks from.

Now I'm not saying that SQL writing is 1970s prompt engineering, but I'm also not not saying that, right?

Here's Don again, after the fact

"Ray and I were wrong about the predominant usage of SQL. Typically, SQL is embedded in a host programming language and used by professional programmers"

Is SQL any good though?

SQL was, as I have said, a spectacular success. It's still bloody everywhere, fifty years on. It was also an abject failure. The syntax is a mess of unaligned clauses with special cases everywhere (INSERT and UPDATE have such radically different approaches to clauses but sort of do the same thing. So does DELETE really). You need to understand maths to do it properly. You also need to understand the precise details of the database schema. The database schema is maintained in a separate dialect that's somehow intertwined with the querying DSL and uses the same interfaces, but again obeys a different syntax and semantics. Record locking is both implicit and explicit. The concurrency model is insane and nobody actually understands it properly. NULL breaks everything including query logic. And most damningly, it's never used as an interactive REPL by non-programmers. It's folded into programs mostly. In fact these days, an eye-wateringly huge number of applications bundle an entire SQLite embedded RDBMS inside their application deployment.

Repeated interface patterns, and why I care

There's a pattern emerging here I think - querying and reporting wasn't quite entirely programming adjacent busywork, but it was business-adjacent drone work, and SQL was an attempt to narrow the interface with an ergonomic DSL that got out of the user's way and reduced the scope of the context switch needed to engage with the reporting system. It kind of failed at the interface, if you ask me (and most folks who have to use it), but it did succeed amazingly at reducing the complexity of the context switch. Using SQL to mediate data persistence inside your application is kind of like using magit to fold your git operations right inside your emacs workflow, they both serve to shrink down the cost of flipping out of your primary task domain, into some other essential, dependent domain.

Either reduce it to a tight DSL, or extract the work and organise it so it can be delegated to another worker. Sometimes, you put a DSL on top of a DSL, to tune it down even further. Sometimes you build a team to own the work in this domain. What if you build a DSL over a DSL but the DSL could sort of work like a team you can delegate tasks to? That's a compelling interface, that is.

When I look at it like this, using an agent REPL in zed to run git operations strongly reminds me of that (failed) SQL/4GL promise. I tell the thing the result I want from it, and it builds a plan of execution, and I can iterate on that, interactively. Only this time, I'm using literal English sentences to describe the narrow domain the system has trained itself on, not some bastard awful pidgin version of it, that somehow ends up with the worst features of both natural languages, and programming languages. Sorry SQL, it has to be said. And you know what, I kind of love you anyway.

I think this pattern can be found in several places of software development, if you squint right. Programming-adjacent work gets reduced with DSLs or narrow abstractions, which bring the benefits of reducing that tedious, expensive context switch. I guess we have lots of it in CI automation, pipeline building, that kind of thing. DevOps is built out of this stuff, infrastructure as code, deployment charts, meta deployment charts, run-books, playbooks. These domains are also places I've found LLM-based assistants super helpful - help me grind out some yaml please so I can add a pull request pipeline that does this thing I just thought of, without me having to spend quite so much time reading up the stupid YAML syntax for this weeks CI system, and spending hours sitting in a push/fail/edit/push loop on some git forge. GraphQL over REST apis - maybe? Unit test generation and test harness design is mostly busywork in a DSL following some declarable constraints. I think I already mentioned figuring out the precise type annotations for things. It makes me think that coding-assistants are perhaps more of a user interface paradigm than they are a coding one. More like a 4GL than a semantic IDE.

In conclusion

What's my point? I'm not completely sure (he says after several thousand words)

- I like zed, I'm finding it more useful than I thought I would, and I've stuck using it on and off for a few months now.

- I keep finding small useful things for LLMs to do, and I enjoy that process.

- The most value might be in 'programming-adjacent' things - e.g. as I mentioned, I'm now personally only writing a small proportion of my commit messages by hand, and I think my commit messages are considerably better off for it.

- Tools that reduce the context switches for 'programming-adjacent' work will win

- Conversational interfaces are very low friction for human minds.

- LLMs are much better than humans at context switching to a different domain, while keeping track of and applying accrued context across different tasks

- Is there something you need to do that applies a tight but boring DSL across a defined data set? A model might actually be quite good at that. Another weird thing I've found them almost spectacularly good at is networking and debugging - describe a topology, give it a tcpdump, and watch it spit out a bunch of diagnostic suggestions and potential remedies for you to use.

- These tools are one of the biggest tech shifts I've seen in my rather long, slightly storied, career that spans a whole bunch of tech paradigm shifts.

Summary footnotes

- This is just some opinions, inspired by how astonished I was to successfully use an "agentic" tool to run some gnarly git stuff I would have had to pull out the manual to do. There's all sorts of important discourse about LLMs and the out of control tech hype cycle around them that I don't go near, and I'm not writing a manifesto

- I'm not a historian, or a first hand witness of the pre-RDBMS data scene, although I did work alongside people who came from that background, so I do have a lot of secondary source exposure. I haven't done much research other than light web searching, so please take my historical characterisations with the appropriate amount of salt. I know pretty much zilch about how IMS/360 actually worked, I just remember the name, I'm generalising.

- I wrote this blog post by hand, it's not the sort of thing I think LLMs are much use at. I'm trying to express my own opinions here, in my own voice, because I was excited about a couple of ideas and wanted to try sharing them

- I wrote this blog post in emacs though.

- I probably won't write any of those other parallel blog posts, who has time to write blog posts?

- I did use Claude to fact check the post. Don't laugh, they can actually do that sort of thing now. This stuff moves fast.

- Finally, I feel I ought to note that Ray Boyce died tragically young at 27 in 1974, shortly after the presentation of the SEQUEL design paper. He left an astonishingly outsize impact after such a short career. Put a dent in the world, as they say. Don Chamberlin, happily, is still with us so far as I know.